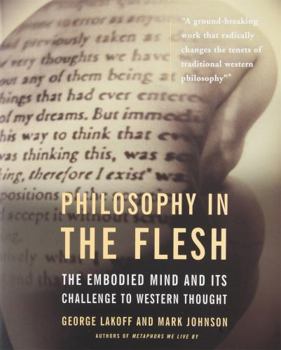

Philosophy in the Flesh

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

What are human beings like? How is knowledge possible? What is truth? Where do moral values come from? Questions like these have stood at the center of Western philosophy for centuries. In addressing them, philosophers have made certain fundamental assumptions-that we can know our own minds by introspection, that most of our thinking about the world is literal, and that reason is disembodied and universal-that are now called into question by well-established results of cognitive science. It has been shown empirically that: Most thought is unconscious. We have no direct conscious access to the mechanisms of thought and language. Our ideas go by too quickly and at too deep a level for us to observe them in any simple way. Abstract concepts are mostly metaphorical. Much of the subject matter of philosophy, such as the nature of time, morality, causation, the mind, and the self, relies heavily on basic metaphors derived from bodily experience. What is literal in our reasoning about such concepts is minimal and conceptually impoverished. All the richness comes from metaphor. For instance, we have two mutually incompatible metaphors for time, both of which represent it as movement through space: in one it is a flow past us and in the other a spatial dimension we move along. Mind is embodied. Thought requires a body-not in the trivial sense that you need a physical brain to think with, but in the profound sense that the very structure of our thoughts comes from the nature of the body. Nearly all of our unconscious metaphors are based on common bodily experiences. Most of the central themes of the Western philosophical tradition are called into question by these findings. The Cartesian person, with a mind wholly separate from the body, does not exist. The Kantian person, capable of moral action according to the dictates of a universal reason, does not exist. The phenomenological person, capable of knowing his or her mind entirely through introspection alone, does not exist. The utilitarian person, the Chomskian person, the poststructuralist person, the computational person, and the person defined by analytic philosophy all do not exist. Then what does? Lakoff and Johnson show that a philosophy responsible to the science of mind offers radically new and detailed understandings of what a person is. After first describing the philosophical stance that must follow from taking cognitive science seriously, they re-examine the basic concepts of the mind, time, causation, morality, and the self: then they rethink a host of philosophical traditions, from the classical Greeks through Kantian morality through modern analytic philosophy. They reveal the metaphorical structure underlying each mode of thought and show how the metaphysics of each theory flows from its metaphors. Finally, they take on two major issues of twentieth-century philosophy: how we conceive rationality, and how we conceive language.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0465056741

ISBN13:9780465056743

Release Date:October 1999

Publisher:Basic Books

Length:640 Pages

Weight:2.43 lbs.

Dimensions:1.7" x 7.3" x 9.1"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

A good, instructive read!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Unlike some of the other critics here, I thoroughly enjoyed this book and, as for those who feel there is a political axe to grind, I did not read that in this book. Perhaps they are thinking of themselves. Here, Lakoff and Johnson look at the role played by metaphor in constructing meaning. They show (adequately, I thought) that our metaphors rely on the manner in which we are embodied. They do not claim these are rigid categories but, rather, that they are flexible and inter-relate. The body, they argue, gives the structure that provides the metaphors. I also detect a lot of partisan philosophy students at work in these reviews. No mention of Santayana? No mention of Nietzsche? Too tough on Kant? The analysis of Kant is given as a brief example and is not intended to be a thesis. As for the others, I am not convinced that Nietzsche shared the concepts that Lakoff and Johnson outline here. And so far as one critic's remark about it taking a man of genius to create a unified vision...that's just disturbing! I think the book is excellent. The shortcomings pointed to seem to have more to do with critic's expectations than the plan for the book. I would, however, have liked to see more on neuro-physiology and on spatial orientation but (once again) that's got more to do with my needs than the purpose of the book. If you enjoy the book then check out Edward Casey's books on space/place, Yi Fu Tuan's "Space and Place", and Shaun Gallagher's "How the body shapes the Mind".

Shame on them for not citing Piaget

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Piaget's concept and work on sensory-motor intelligence and development of ideas, genetic epistemology etc. clearly anticipates them.

Another nail in Plato's coffin

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

Lakoff and Johnson's book "Philosophy in the Flesh" adds the voice of cognitive linguistics to the growing chorus of voices from science of mind that have informed philosophers: the Platonic World View is nearing the end of its reign over Western philosophy. The human mind is a product of its physical embodiment in the flesh, not some non-physical mystery.In addition to its main story line, "Philosophy in the Flesh" also has a meta-story line. Lakoff and Johnson were well aware of the fact that many philosophers who remain bewitched by the West's Platonic legacy do not want to listen to what the science of mind has discovered. As Lakoff and Johnson clearly explain the situation, Platonic Idealism, Cartesian Dualism, and Anglo-American analytic philosophy are the natural products of a priori philosophical assumptions that are based on certain common sense metaphors such as 'seeing is believing'. Lakoff and Johnson carefully explain how the science of cognitive linguistics has accumulated data that show the limitations of such Folk Psychological views. Within "Philosophy in the Flesh", Lakoff and Johnson included an anticipatory critique of their critics, explaining why these critics remain trapped in a dead-end philosophical world view. The key point is that many philosophers are still trained in the belief that science can have nothing useful to say about the mind. This attitude towards science is a fundamental part of the philosophical tradition that is invalidated by modern science of mind. Thus, we are dealing with the latest installment in the rather intriguing situation of an entire intellectual nation being declared intellectually bankrupt by another intellectual tribe. A perfect setting for a protracted battle! In addition, Lakoff and Johnson explicitly explain what is wrong with postmodernism and why it is at odds with their views. Amazingly, this has not stopped some from calling Lakoff's and Johnson's approach postmodern. There is exceptional irony in this kind of desperate attack on the ideas expressed in "Philosophy in the Flesh".The meta-story line within "Philosophy in the Flesh" serves a useful role for potential buyers of the book. Many critics of "Philosophy in the Flesh" are adherents to the Platonic World View and they have voiced exactly the complaints about "Philosophy in the Flesh" that Lakoff and Johnson explicitly anticipated and accounted for with their meta-story line. What can we conclude when these critics of "Philosophy in the Flesh" fail to mention the meta-story line and how it anticipated their complaints? Most likely, such critics of this book did not read it. If they had, they would have seen the meta-story line and addressed IT in their reviews of the book.If you are a member of the anti-science tribe of philosophers of mind and language, you will have been trained to ignore the arguments and scientific data that are presented by Lakoff and Johnson. If you are already devoted to an investigation of mind and lang